Oga for Depression a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- Inquiry commodity

- Open Admission

- Published:

Yoga for prenatal depression: a systematic review and meta-assay

BMC Psychiatry volume xv, Article number:14 (2015) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Prenatal depression tin can negatively bear upon the physical and mental health of both mother and fetus. The aim of this study was to decide the effectiveness of yoga as an intervention in the direction of prenatal depression.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-assay of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was conducted by searching PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library and PsycINFO from all retrieved articles describing such trials up to July 2014.

Results

Six RCTs were identified in the systematic search. The sample consisted of 375 significant women, nigh of whom were between 20 and xl years of age. The diagnoses of depression were adamant by their scores on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-Four and the Middle for Epidemiological Studies Low Scale. When compared with comparison groups (due east.1000., standard prenatal care, standard antenatal exercises, social support, etc.), the level of low statistically significantly reduced in yoga groups (standardized hateful difference [SMD], −0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.94 to −0.25; p = 0.0007). One subgroup analysis revealed that both the levels of depressive symptoms in prenatally depressed women (SMD, −0.46; CI, −0.ninety to −0.03; p = 0.04) and non-depressed women (SMD, −0.87; CI, −1.22 to −0.52; p < 0.00001) were statistically significantly lower in yoga grouping than that in control group. At that place were ii kinds of yoga: the physical-do-based yoga and integrated yoga, which, besides physical exercises, included pranayama, meditation or deep relaxation. Therefore, the other subgroup assay was conducted to estimate effects of the two kinds of yoga on prenatal low. The results showed that the level of low was significantly decreased in the integrated yoga group (SMD, −0.79; CI, −1.07 to −0.51; p < 0.00001) but not significantly reduced in physical-practice-based yoga grouping (SMD, −0.41; CI, −1.01 to −0.18; p = 0.17).

Conclusions

Prenatal yoga intervention in significant women may be effective in partly reducing depressive symptoms.

Background

In Korea, 8%-12% of all pregnant women endure with major depressive disorder (MDD), and about 20% have clinically significant depressive symptoms, which do not encounter the criteria for MDD [i]. In the US, information technology is estimated that the prevalence of antenatal depression reaches x–twenty% [2]. Indeed, prenatal low is estimated to occur in 6–38% of pregnancies in unlike countries [3]. Prenatal low, i.e., depressive episode during pregnancy, is undoubtedly a serious threat to the health of pregnant women all over the earth. One study of 277 pregnant women indicated an antepartum low rate of almost 20%, which was near double that of the eleven% rate observed after commitment [4]. Withal, prenatal depression has been studied much less than postnatal depression [5]. Prenatal depression may negatively affect the physical and mental health of both mother and fetus [vi]. For example, children of depressed mothers show lower birth weights, elevated resting heart rates, increased risk of developmental delays and prematurity, increased physiological reactivity, and more behavior problems in childhood and boyhood than children of non-depressed mothers [7-eleven]. Besides, prenatal depression has been regarded every bit the strongest risk factor for postnatal depression [12] and a mediator betwixt risk factors and postnatal low [13]. All of these highlight the necessity of prenatal interventions for depressed symptoms during pregnancy.

Antidepressant therapy can reduce symptoms of prenatal depression, merely its safety has been controversially discussed for many years. Antidepressants may increase the run a risk of postpartum hemorrhage and harmfully bear upon the unborn child, therefore, they are not always safe during pregnancy [fourteen,fifteen]. Pregnancy is a major determinant of the abeyance of antidepressant medication [16]. Only a small number of pregnant women with depressive disorders are using antidepressants considering of the mixed information on fetal and neonatal outcomes [17]. Both psychotherapy and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) are popular therapies. Psychological treatments for perinatal depression are extensively used, and take shown benefits in some studies [xviii]. CAM comprises a broad array of unlike treatments, ranging from herbal medicine to yoga. Many women are comfortable using CAM during pregnancy since these treatment options appear to be potentially useful for improving psychological health during pregnancy [19,xx]. Nearly patients practise believe that CAM treatments are prophylactic and effective [21]. Notably, in Israel, nearly obstetricians show positive attitudes to these treatments and recommend using them during pregnancy [22].

With the goal of achieving the highest possible functional harmony between trunk and heed, the Indian yoga encompasses various domains, including upstanding disciplines, concrete postures and spiritual practices. All aspects of yoga practice contribute to a land of deep relaxation in which both the torso and mind experience calmness [23]. In the United States, fifteen meg adults have been practicing yoga, with almost half using yoga to prevent wellness problems, promote wellness or manage a specific health condition [24]. Contempo studies indicate that yoga tin meliorate life quality in physical atmospheric condition such as cancer [25], menopause [26] and pain [27]. Yoga intervention as well plays a vital role in preventing mental disorders such as refractory epilepsy [28], schizophrenia [29], feelings of sadness [thirty], depression and anxiety disorders [23]. Moreover, the efficacies of yoga on pregnant women (e.g., reduce perceived stress, heighten immune function, improve adaptive autonomic response to stress, etc.) [31,32] and pregnancy result (e.g., gestational age at commitment, mode of commitment, intrauterine growth retardation, etc.) [33] have been identified. Especially, yoga has been shown to increase gestational age and birth weight [34], amend maternal comfort during labor [27], facilitate normal commitment, subtract complications, labor elapsing, and anesthesia requirements [27,33].

Here, nosotros examined the testify that yoga (exercise-based yoga and integrated yoga) may improve the depressive symptoms of pregnant women. This systematic review was carried out basing on several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published upwardly to July 2014.

Methods

Search strategy

An Internet-based search was performed through PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library and PsycINFO from all retrieved articles up to July 2014. For PubMed and Embase, the following search terms were used: the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) or Emtree terms "depression", "depressive disorder", "mood disorder", "prenatal depression", "pregnancy", "prenatal intendance", "pregnancy complications" and "yoga" and the respective costless terms. For the Cochrane Library and PsycINFO, the correlative keywords were used. Terms were moderately expanded within each electronic database whenever necessary. No language restrictions were applied.

Inclusion and exclusion

Inclusion criteria included RCTs of pregnant women who were randomized to yoga and comparison groups. There were no strict restrictions on comparing groups. Therefore, whatever trials that compared yoga to usual intendance or whatsoever other concrete or mental care (eastward.g., standard prenatal intendance, standard antenatal exercises, social support, etc.) were eligible. There are a number of different types of yoga being taught and practiced today. Some merely included physical practice, such every bit stretching, savasana, or other asana postures. In add-on to physical practice, other kinds of yoga, which were defined every bit integrated yoga, as well included pranayama, meditation or deep relaxation. Therefore, both physical-practice-based yoga and integrated yoga were accustomed and evaluated in a subgroup analysis. The meaning women who participated in the trials were either depressed or non depressed. Differences between the two types of pregnant participants were as well investigated in the other subgroup analysis. Exclusion criteria included nonrandomized or uncontrolled trials, postpartum depression, nonetheless incomplete articles after contacting the authors, trials based on in vitro fertilization (IVF), treatment with medicine too yoga, and antenatal depression pooled with other constructs. These choice criteria were confirmed co-ordinate to the results of searching.

Information extraction

Data extraction was completed by iii authors (HG, CN and TW) using a standard extraction form. Outset, ii authors independently extracted the data. Then, the third author compared their results and discussed with them to accomplish a consensus. Only those original articles, which not just fulfilled the inclusion criteria, but also did not meet the exclusion criteria, were regarded every bit qualified. The extraction class included the following information: publication twelvemonth, country, the number of participants, the age and gestation of participants, the measurement of depression before and after intervention, toll, percent of primiparous women in each group, exclusion criteria, the results of trials and the protocol of intervention grouping (the type of yoga, program length, frequency, elapsing, practice way, etc.).

Quality assessment

Two qualified reviewers (HG and CN) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. The quality assessment organization was modified from the criteria of Juni and Stroup et al. [35,36], which included eligibility criteria, randomization, allotment concealment, lost to follow-upwardly, intension-to-treat analysis and outcome assessor blinding. Every bit this was an interventional study and it was quite difficult for the researchers to deport the blinding of participant and provider, participant blinding and provider blinding were excluded in the score system. Nevertheless, blinding of the effect assessor could be adequate and it was included.

The quality of each study was assessed as "yeah", "unclear", or "none". The more criteria a study met the higher quality information technology had. Studies that met all the criteria were ranked every bit A. On the contrary, those could not meet any criteria were ranked every bit C. The remaining ones were ranked as B [37]. Some other author (XS) participated in the discussion on the divided opinion, until an agreement was reached.

Since this study was a literature review of previously reported studies, ethical approval or boosted consent from participants was not required.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Most results of the trials but reported the pre-intervention and post-intervention means and standard deviations (SDs). Nonetheless, the changes during the interventions were not reported. Although the trials were randomized, different baselines might still exist. Using the final mean and SD to clarify it was not accurate. According to the previous studies [38,39], a correlation coefficient of 0.6 was used to calculate the irresolute SD during the interventions. The adding formula was based on the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [twoscore].

Review Manager v software (version 5.iii, The Nordic Cochrane Eye, Copenhagen, Denmark) for Windows package was used to analyze the data. For continuous outcomes, standardized hateful differences (SMDs) with 95% conviction intervals (CIs) were calculated as the differences in means, and α = 0.05 was used as the statistical pregnant level. A stock-still effects model was initially adopted to summate χ2 and I2 to test for heterogeneity. It was regarded as notable heterogeneity, when I2 was valued at more than l%. Since the random furnishings model is more conservative than the stock-still effects model, a random effects model should be used unless it exhibited depression heterogeneity [40,41]. Subgroup comparisons were besides carried out to analyze the depression levels of different types of yoga and participants. The funnel plot, which is a besprinkle plot, has been used frequently to guess the take a chance of publication bias. We did not use a funnel plot considering of the express number of included studies.

Results

Systematic review

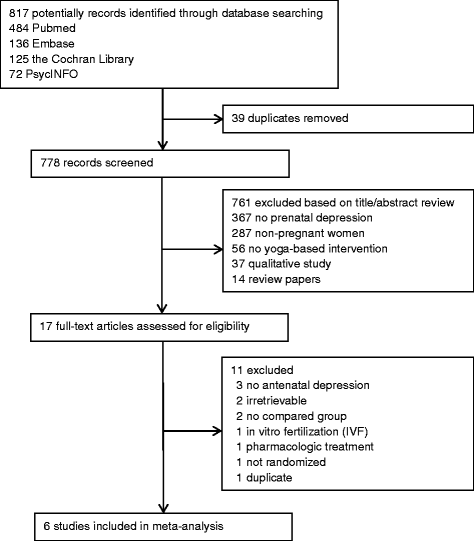

Of the 817 potentially relevant articles from the electronic database, but six were retained for assay while the remaining 811 were excluded. Most were excluded considering they were not relevant to prenatal depression (n = 367) or did not involve pregnant women (n = 287). For studies that were read in total text and assessed for eligibility, three were non near antenatal depression and were excluded [42-44], two were unable to obtain [45,46] (Effigy 1), two reported without any controlled groups [47], one was in vitro fertilization (IVF) [48], one was treated with medicine [49], one did not indicate that randomization was conducted [fifty] and one [51] was already included in the present written report [52]. Therefore, six RCTs (375 cases total) that compared the yoga groups with control groups for depression were finally included.

Flow chart of report selection in meta-analysis.

The characteristics of the six articles are shown in detail (please run across Additional file one: Table S1.) Most articles originated from the United states of america, while only one from India and another from United Kingdom. All of those six RCTs were published in the past five years. 4 RCTs included depressed patients with a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-Four (SCID) diagnosis of low [53-56], while the other two trials enrolled normal or non-depressed meaning women [52,57]. Three RCTs used exercise-based yoga [53,54,56], the other 3 RCTs used complex yoga interventions, including tai chi [55], relaxation, meditation [57], and breathing exercises [52]. Those RCTs mainly used Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [53-56], Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) [57] and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [52] to measure the level of depression. Results of some articles showed significant differences favoring yoga over control groups [52-54,57], while others did not [55,56].

Quality of included studies

Nigh included trials were non of loftier quality. All of them were randomly assigned to either a yoga handling or a control group, but simply ii of them explained the randomization method [52,57]. Four RCTs reported the number of lost participants in each group and stated reasons for each case [52,55-57], but the remaining RCTs did not clarify this issue [53,54]. The allocation concealment and intension-to-treat analysis were not mentioned in most RCTs, except one [52]. As noted earlier, because it seemed impossible to adopt participant blinding and provider blinding in yoga intervention, simply blinding of the upshot assessor was included. Adequate issue assessor blinding was conducted in three RCTs [51,54,55]. All of the RCTs described the inclusion and exclusion criteria in detail. Three RCTs showed similar baseline [52,56,57], while the others did not [53-55]. The results of quality cess are provided in this study (please see Additional file 2: Table S2).

Meta-analysis

Analysis of overall effect

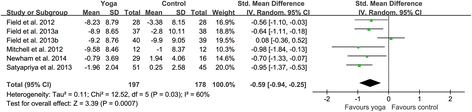

Overall, six comparisons were made for depression. The results showed that in that location was a significant heterogeneity, as was evident from I2 = 60% (p = 0.03). When using a random effects model, the standardized weight mean divergence (SMD) was −0.59 (95% CI, −0.94 to −0.25), which was a significant effect in favor of yoga (p = 0.0007) (Figure ii).

Forest plots of effects of yoga on prenatal depression scores. Woods plot of the comparing of the yoga intervention group versus the control group for prenatal low scores.

Subgroup analyses

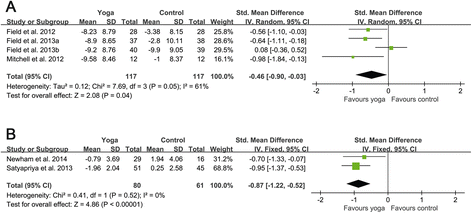

Co-ordinate to unlike types of participants and yoga interventions, two subgroups were created respectively. For different types of participants, four RCTs included pregnant women with depressive symptoms [53-56], while the remaining two RCTs included women without depressive symptoms [52,57]. Pooling trials according to the types of participants gave standardized mean difference of −0.46 (−0.90 to −0.03) for depressed women and −0.87 (−one.22 to −0.52) for non-depressed women (Effigy three). For the subgroup of depressed women, a random effects model was used, because there was a sure degree of heterogeneity within this subgroup (Itwo = 61%, p = 0.05). While a fixed effects model was used in the subgroup of non-depressed women since there was no significant evidence of heterogeneity in this subgroup (I2 = 0, p = 0.52). The results of this meta-analysis indicated that both the levels of depressive symptoms in prenatally depressed women (p = 0.04) and non-depressed women (p < 0.00001) were statistically significantly lower in yoga groups than that in control groups.

Forest plots of furnishings of yoga on depression scores for prenatally depressed and non-depressed women. (A) Wood plot of the comparison of the yoga intervention group versus the control group for low scores in prenatally depressed women. (B) Woods plot of the comparison of the yoga intervention group versus the control group for low scores in prenatally non-depressed women.

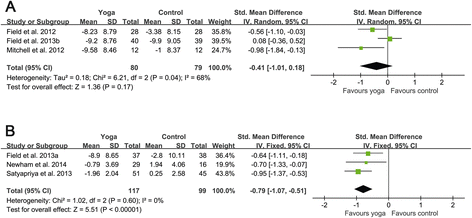

Every bit to yoga interventions, 3 RCTs adopted do-based yoga [53,54,56]; the remaining iii RCTs adopted the integrated yoga [52,55,57]. Pooling trials according to the types of yoga interventions gave standardized mean divergence of −0.41 (−1.01 to 0.18) for exercise-based yoga and −0.79 (−i.07 to −0.51) for integrated yoga (Figure iv). There was a certain degree of heterogeneity in the subgroup of exercise-based yoga (Itwo = 68%, p = 0.04), while the heterogeneity in the subgroup of integrated yoga was not evident (I2 = 0, p = 0.60). The results of this meta-analysis revealed that the depression level of the exercise-based yoga group was non statistically significantly reduced (p = 0.17). Notwithstanding, the depression level of the integrated yoga group was significantly decreased (p < 0.00001).

Forest plots of effects of practise-based yoga and integrated yoga on prenatal depression scores. (A) Wood plot of the comparison of the exercise-based yoga group versus the control group for prenatal depression scores. (B) Wood plot of the comparison of the integrated yoga group versus the command group for prenatal low scores.

Discussion

Using an exhaustive and comprehensive search strategy, we identified six moderate quality RCTs to evaluate the intervention of yoga for prenatal depression. This study demonstrates that yoga can exist helpful for pregnant women to alleviate symptoms of depression. Analysis of overall consequence indicated that yoga intervention significantly reduced the level of maternal low before parturition. Besides, the command groups of some included studies received some forms of social back up or massage rather than usual care. Since these interventions are not belonging to simple usual intendance, the true event of yoga may exist underestimated.

In club to effigy out the potentially diverse furnishings of yoga, these studies were divided by the types of participants and yoga interventions. A subgroup assay of depressed and non-depressed women showed that both types apparently benefited from yoga treatment for antenatal depression. Results of the other subgroup revealed that integrated yoga intervention significantly reduced the level of prenatal depression, simply the exercise-based yoga did not. The SMDs with 95% CIs were −0.79 (−one.07, −0.51) and −0.41(−1.01, 0.18), respectively. As a consequence, compared with practice-based yoga, the integrated yoga may be a improve choice for pregnant women.

Previous meta-analysis has found the limited-to-moderate evidence for short-term improvements of depression and anxiety in severity [58], but in that location are not whatsoever reports well-nigh prenatal low. Some other meta-analysis focused on exercise for antenatal low, and showed a significant reduction in depression scores (SMD −0.46, 95% CI −0.87 to −0.05, p = 0.03, I2 = 68%) for do intervention relative to the comparison group [38]. However, Satyapriya et al. [57] reported that the depression level of yoga intervention grouping was significantly lower than that in the exercise group. Therefore, yoga seems useful to alleviate prenatal depression, and the results show that integrated yoga may be even more effective.

This meta-analysis included six moderate quality RCTs. Participants were recruited at their first or second ultrasound cess (about 20 weeks gestation), including Hispanic, African-American, white and a few other races in the United States, India and the Britain. The inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria of these RCTs were similar. All of the depressed participants met diagnostic criteria for depression on SCID. Nigh of the RCTs used the same rating scales to measure depression (CES-D). The program lengths of yoga and control groups of the vi RCTs were about 12 weeks.

This report also has several limitations. Offset of all, since the baselines of each study were not exactly the same and the methods to generate random sequence were non clearly antiseptic in most trials, the selection biases cannot be controlled efficiently. Also, most RCTs used CES-D to measure the levels of depression, while 1 RCT used HADS [57] and some other used EPDS [52]. The variable methods of measuring and reporting depression may contribute to a certain degree of heterogeneity. Using CES-D and SCID to assess pregnant women's low is not the best pick due to misinterpretation of somatic symptoms of pregnancy for sure items (due east.g., tiredness, lack of energy). Instead, using Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) will be amend. Some other potential drawback involves the outcome of report dropouts on the validity of study findings. In addition, trials with negative results are less likely to be published and more likely to be excluded from systematic review, which induces the literature towards positive findings. Finally, this study included 6 trials and 375 pregnant women. The small sample size may possibly lead to false positive conclusion.

More attending should be paid to use the standardized yoga as an intervention in future research, which may contribute to find out the best fashion to prevent and treat prenatal depression.

Conclusions

With the limitations in mind, this article allows usa to depict several conclusions regarding yoga for prenatal low. Firstly, prenatal yoga may exist helpful to decrease maternal depressive symptoms. Secondly, both the depressed and not-depressed pregnant women tin can do good from yoga. Lastly, the integrated yoga seems more than effective in treating depression than physical-do-based yoga.

References

-

Park CM, Seo HJ, Jung YE, Kim MD, Hong SC, Bahk WM, et al. Factors associated with antenatal depression in meaning Korean females: the effect of bipolarity on depressive symptoms. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;x:1017–23.

-

Fellenzer JL, Cibula DA. Intendedness of pregnancy and other predictive factors for symptoms of prenatal low in a population-based study. Matern Child Wellness J. 2014;18(x):2426–36.

-

Previti Thousand, Pawlby S, Chowdhury Southward, Aguglia E, Pariante CM. Neurodevelopmental outcome for offspring of women treated for antenatal depression: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(half dozen):471–83.

-

de Tychey C, Spitz E, Briancon South, Lighezzolo J, Girvan F, Rosati A, et al. Pre- and postnatal depression and coping: a comparative approach. J Affect Disord. 2005;85(3):323–six.

-

Matthey Southward, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum low in mothers and fathers: whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disord. 2003;74(2):139–47.

-

Glover V. Maternal stress or anxiety in pregnancy and emotional development of the child. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:105–six.

-

de Bruijn AT, van Bakel HJ, van Baar AL. Sex differences in the relation between prenatal maternal emotional complaints and child outcome. Early on Hum Dev. 2009;85(five):319–24.

-

Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, Emond A. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early on child development. BJOG. 2008;115(8):1043–51.

-

Field T, Deeds O, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif One thousand, Gauler A, Sullivan Southward, et al. Benefits of combining massage therapy with grouping interpersonal psychotherapy in prenatally depressed women. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2009;xiii(4):297–303.

-

Allister L, Lester BM, Carr Due south, Liu J. The effects of maternal depression on fetal heart charge per unit response to vibroacoustic stimulation. Dev Neuropsychol. 2001;20(3):639–51.

-

Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Cullen C, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Prepartum, postpartum, and chronic low effects on newborns. Psychiatry. 2004;67(i):63–80.

-

Heron J, O'Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V. The class of anxiety and low through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2004;lxxx(one):65–73.

-

Leigh B, Milgrom J. Run a risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC psychiatry. 2008;viii:24.

-

Campagne DM. Fact: antidepressants and anxiolytics are not condom during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;135(2):145–8.

-

Palmsten K, Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Williams PL, Michels KB, Achtyes ED, et al. Use of antidepressants near delivery and risk of postpartum hemorrhage: accomplice written report of low income women in the United States. BMJ. 2013;347:f4877.

-

Petersen I, Gilbert RE, Evans SJ, Human SL, Nazareth I. Pregnancy equally a major determinant for discontinuation of antidepressants: an analysis of data from The Health Improvement Network. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(7):979–85.

-

Einarson A, Choi J, Einarson TR, Koren M. Adverse furnishings of antidepressant use in pregnancy: an evaluation of fetal growth and preterm nascence. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(1):35–8.

-

Stuart S, Koleva H. Psychological treatments for perinatal low. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28(1):61–70.

-

Newham JJ. Complementary therapies in pregnancy: a means to reduce sick health and improve well-being? J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2014;32(three):211–3.

-

Hall HG, Griffiths DL, McKenna LG. The utilize of complementary and culling medicine by pregnant women: a literature review. Midwifery. 2011;27(6):817–24.

-

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay Thou, et al. Trends in culling medicine employ in the United states, 1990–1997: results of a follow-upwards national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569–75.

-

Samuels North, Zisk-Rony RY, Many A, Ben-Shitrit G, Erez O, Mankuta D, et al. Use of and attitudes toward complementary and culling medicine amongst obstetricians in Israel. Int J Gynaecol Obste. 2013;121(2):132–6.

-

Taso CJ, Lin HS, Lin WL, Chen SM, Huang WT, Chen SW. The effect of yoga exercise on improving depression, feet, and fatigue in women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Res. 2014;22(3):155–64.

-

Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Culpepper L, Phillips RS. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga utilize in the United States: results of a national survey. Altern Ther Wellness Med. 2004;x(ii):44–9.

-

Smith KB, Pukall CF. An evidence-based review of yoga every bit a complementary intervention for patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(v):465–75.

-

Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos Yard. Effectiveness of yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:863905.

-

Chuntharapat South, Petpichetchian Due west, Hatthakit U. Yoga during pregnancy: effects on maternal condolement, labor pain and birth outcomes. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;xiv(2):105–15.

-

Sathyaprabha TN, Satishchandra P, Pradhan C, Sinha Southward, Kaveri B, Thennarasu Chiliad, et al. Modulation of cardiac autonomic balance with adjuvant yoga therapy in patients with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12(2):245–52.

-

Cramer H, Lauche R, Klose P, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Yoga for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-assay. BMC psychiatry. 2013;13:32.

-

Telles Southward, Singh North, Joshi 1000, Balkrishna A. Mail service traumatic stress symptoms and heart rate variability in Bihar flood survivors post-obit yoga: a randomized controlled written report. BMC psychiatry. 2010;10:18.

-

Satyapriya M, Nagendra 60 minutes, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha 5. Upshot of integrated yoga on stress and heart rate variability in pregnant women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104(3):218–22.

-

Field T. Yoga clinical research review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(1):one–8.

-

Narendran S, Nagarathna R, Narendran V, Gunasheela Southward, Nagendra Hour. Efficacy of yoga on pregnancy outcome. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;eleven(ii):237–44.

-

Babbar Due south, Parks-Savage AC, Chauhan SP. Yoga during pregnancy: a review. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(six):459–64.

-

Juni P, Altman DG, Egger One thousand. Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323(7303):42–6.

-

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-assay of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

-

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical bear witness of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment furnishings in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273(5):408–12.

-

Daley A, Foster 50, Long 1000, Palmer C, Robinson O, Walmsley H, et al. The effectiveness of exercise for the prevention and treatment of antenatal depression: systematic review with meta-analysis. BJOG. 2015;22(ane):57–62.

-

Ussher M, Aveyard P, Manyonda I, Lewis S, West R, Lewis B, et al. Physical activity as an assist to smoking cessation during pregnancy (Spring) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;xiii:186.

-

Higgins JPT GS, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011.

-

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–lx.

-

Rakhshani A, Maharana Southward, Raghuram N, Nagendra 60 minutes, Venkatram P. Effects of integrated yoga on quality of life and interpersonal relationship of pregnant women. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(10):1447–55.

-

Deshpande C, Rakshani A, Nagarathna R, Ganpat T, Kurpad A, Maskar R, et al. Yoga for high-adventure pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(three):341–4.

-

Uchiyama G, Aoyama F, Sakane S. Active direction of pregnant patients and natural childbirth. Function I. Preparation for childbirth and yoga (based on "Prenatal Yoga and Natural Childbirth" by J. O. Medvin. Josanpu Zasshi. 1979;33(4):263–viii.

-

Davis KJ. The feasibility of yoga in the handling of antenatal low and anxiety: A pilot study. ProQuest Information & Learning: US; 2014.

-

Battle C, Uebelacker LA. Evolution of a yoga intervention for antenatal low. Arch Women Ment Hlth. 2013;16:S64.

-

Muzik M, Hamilton SE, Lisa Rosenblum K, Waxler Due east, Hadi Z. Mindfulness yoga during pregnancy for psychiatrically at-run a risk women: preliminary results from a pilot feasibility written report. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012;18(4):235–40.

-

Shim CS, Lee YS. [Effects of a yoga-focused prenatal program on stress, anxiety, self confidence and labor hurting in meaning women with in vitro fertilization treatment]. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012;42(3):369–76.

-

Kloos AL, Dubin-Rhodin A, Sackett JC, Dixon TA, Weller RA, Weller EB. The impact of mood disorders and their treatment on the pregnant adult female, the fetus, and the infant. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(two):96–103.

-

Bershadsky S, Trumpfheller L, Kimble HB, Pipaloff D, Yim IS. The effect of prenatal Hatha yoga on affect, cortisol and depressive symptoms. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2014;20(2):106–13.

-

Newham JJ, Aplin JD, Wittkowski A, Westwood M. Efficacy of yoga in reducing maternal anxiety in pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2010;17(iii):200A.

-

Newham JJ, Wittkowski A, Hurley J, Aplin JD, Westwood K. Effects of antenatal yoga on maternal anxiety and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(8):631–xl.

-

Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif Thou, Medina L, Delgado J, Hernandez A. Yoga and massage therapy reduce prenatal depression and prematurity. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2012;16(2):204–9.

-

Mitchell J, Field T, Diego M, Bendell D, Newton R, Pelaez Yard. Yoga reduces prenatal low symptoms. Psychology. 2012;iii(9A):782–half-dozen.

-

Field T, Diego Yard, Delgado J, Medina 50. Tai chi/yoga reduces prenatal depression, feet and sleep disturbances. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19(ane):half-dozen–10.

-

Field T, Diego M, Delgado J, Medina L. Yoga and social back up reduce prenatal low, anxiety and cortisol. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013;17(iv):397–403.

-

Satyapriya One thousand, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V, Nagendra HR. Effect of integrated yoga on feet, depression & well being in normal pregnancy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19(four):230–6.

-

Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos Yard. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-assay. Depress Anxiety. 2013;thirty(xi):1068–83.

Acknowledgements

This enquiry was supported by grants from the Armed forces Enquiry Foundation (BWS14J021) and National Instrumentation Program (2013YQ190467). The authors would like to thank Guangrong Song and Weidong Pi for their assistance with the literature search for this review. The authors also appreciate James Newham for responding to our requests for the original data.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HG contributed to study design, data extraction, quality assessment, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the manuscript. CN contributed to study design, information extraction, quality assessment, analysis and estimation of data, and drafting the manuscript. XS contributed to study design, quality cess and analysis, interpretation of information and revising the article. TW contributed to study blueprint, data extraction, analysis and interpretation of data. CJ contributed to conceiving the report, participating in written report design and revising the article. All authors proofed and approved the submitted version of the article.

Hong Gong, Chenxu Ni and Xiaoliang Shen contributed equally to this piece of work.

Additional files

Boosted file 1: Table S1.

Characteristics of 6 studies included in the meta-analysis. CES-D, Heart for Epidemiological Studies Depression Calibration; Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; IVF, In Vitro Fertilization; IUGR, Intrauterine Growth Retardation; TAU, treatment-as-usual; POMS, Profile Of Mood States; HADS, Infirmary Anxiety Depression Calibration; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Low Scale.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Quality assessment of the studies included.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits employ, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other 3rd political party material in this article are included in the article'due south Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the fabric. If textile is non included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, yous volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a re-create of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zilch/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this commodity

Cite this article

Gong, H., Ni, C., Shen, X. et al. Yoga for prenatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 15, 14 (2015). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12888-015-0393-1

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12888-015-0393-1

Keywords

- Yoga

- Prenatal depression

- Systematic review

- Meta-assay

Source: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-015-0393-1

0 Response to "Oga for Depression a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis"

Post a Comment